Xavier Mertz – Swiss polar explorer and science diplomat

Xavier Mertz was the first Swiss polar explorer to set foot in Antarctica in 1911, but his drive to explore the region came at a bitter price. Although polar exploration today is less dramatic, it is even more urgent than ever before. To mark Swiss Polar Day, the head of the FDFA's Prosperity and Sustainability Division, Stefan Estermann, talks about the role Swiss polar research has to play and how Switzerland is stepping up its commitment to scientific diplomacy.

The only memorial to Dr Xavier Mertz and Lt Belgrave Ninnis for a long time: a cross on their base camp at the time, Cape Denison. © Mawson's Hut Foundation

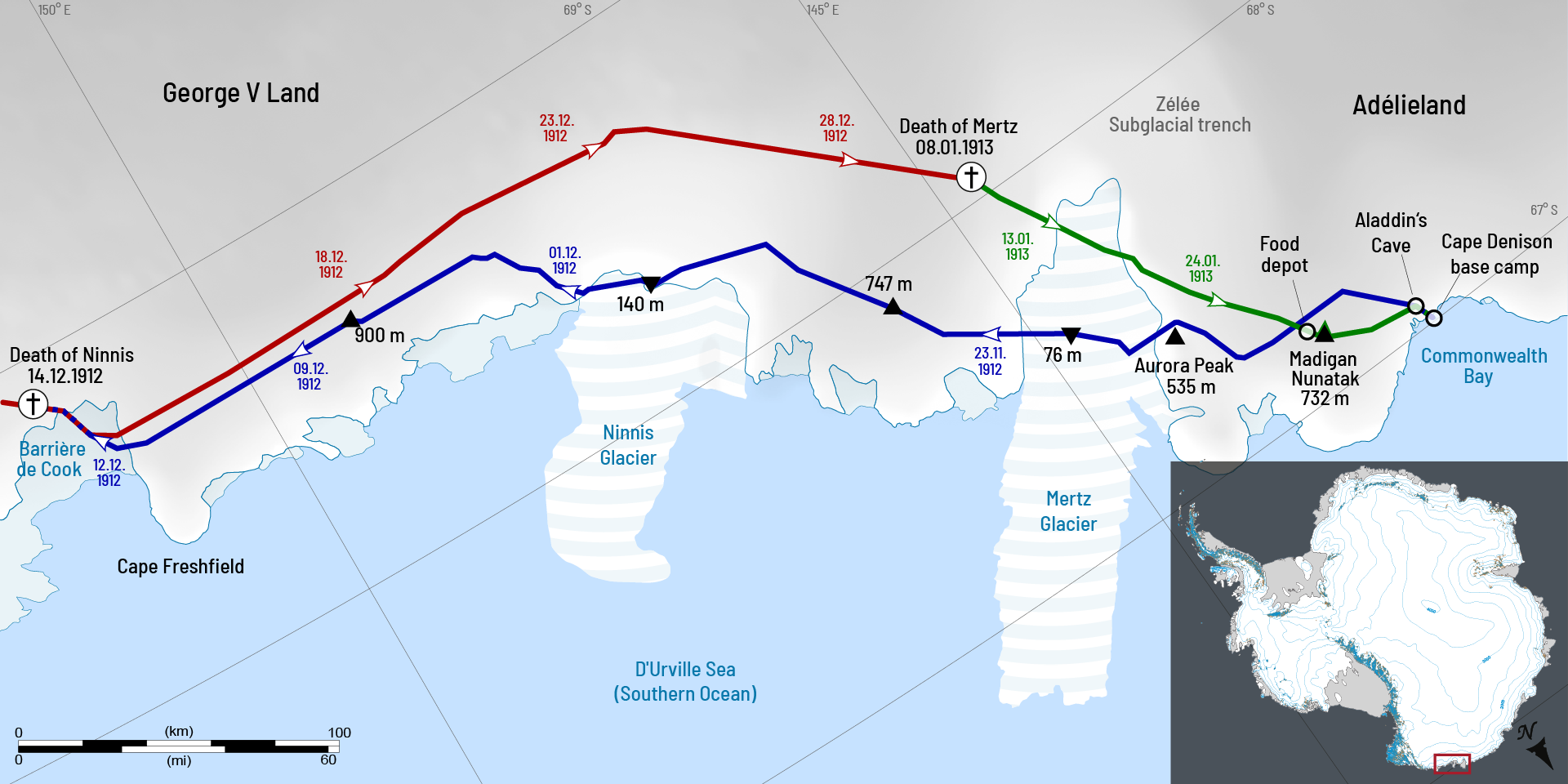

His friend Ninnis has just died, disappearing down a never-ending icy ravine. They had been making good progress before that – the expedition team had managed to advance about 500km into East Antarctica, a place no human being had ever set foot in before. The three men in the team are the Australian Douglas Mawson, the leader of the expedition, Belgrave Ninnis from Britain, and the Swiss researcher Xavier Mertz. The conditions are hard. It is 14 December 1912, when the Antarctic summer hovers between zero and minus 20 Celsius. The severe winds flowing out from the polar plateau generate cold air rushes of up to 350kmph, endangering humans, animals and equipment alike.

Now there's just the two of them. When Ninnis disappeared, he took the heavier sledge carrying most of the equipment, food and the strongest dogs with him. The tragedy was just waiting to happen. Ninnis was visibly getting worse; both he and Mawson had already fallen into several crevasses with their sledges and dogs. Although they were rescued each time, the food for the dogs was lost early on. This meant they had to kill the weaker dogs to feed the others. Newborn dogs suffered the same fate.

500km back to reach safety at base camp

The loss of their friend weighs heavily on Mawson and Mertz, who now have to turn back because of the lack of food, dogs and equipment. They are forced to kill more dogs: this time to feed themselves. Although the flesh of the weakened dogs is tough, the offal – especially the liver – is edible enough. After making initial progress, Mertz's condition deteriorates visibly. Forty-nine days after setting out on the expedition, Mertz records in his journal that he is no longer able to write. It will be his last entry.

Mertz collapses six days later. Mawson tries to pull him along on the sledge but is soon forced to shelter in the tent because of high winds. After falling into a delirium lasting several hours, Dr Xavier Mertz – lawyer, glaciologist and mountaineer – dies on 8 January 1913. The actual cause of his death is never fully clarified, but is thought to have been due to poisoning from eating the Greenland huskies' livers.

Mawson is now forced to carry on alone. Because of Mertz's death, he actually has more rations for himself and is able to cross for a second time what will later be known as Mertz Glacier. On 8 February 1913, after 90 days in the eternal ice, Mawson finally makes it back to base camp – on his hands and knees.

In remembrance of the first Swiss polar explorer in Antarctica

Mertz was the first Swiss polar explorer to set foot in Antarctica. In addition to the Cape Denison cross erected at the time, in May 2021 a commemorative plaque in memory of Ninnis and Mertz was inaugurated in Tasmania's Hobart harbour by the Swiss ambassador and British high commissioner to Australia.

Swiss Polar Day

In 2020 Switzerland and Australia signed an agreement giving Swiss research institutions access to Antarctica via the Swiss Polar Institute, a foundation that promotes Swiss polar research. Swiss Polar Day, an annual networking event for the Swiss polar and high-altitude research community, is held on 1 October each year.

The polar caps are like the engine room of the world's climate. This means that polar research can help us understand climate change and thereby find ways to combat it. Switzerland's foreign policy strategy includes climate change as one of its objectives, as does the UN's 2030 Agenda.

Science diplomacy – a win-win for research and diplomacy

Global challenges like climate change require global cooperation. The relatively new field of science diplomacy makes this possible by improving collaborative efforts between researchers as well as relations between countries in general. The Swiss-Australian agreement on scientific cooperation advances research but can also work the other way round, helping to improve interstate relations and dialogue based on such collaborative frameworks. A good example is the Arctic Council, which focuses on the exploration and protection of the Arctic and brings together all the countries with sovereignty over part of the region – from Russia and northern Europe to Canada and the US.

The goal of the FDFA's science diplomacy is to support Swiss researchers to such ends. Stefan Estermann, ambassador and head of the Prosperity and Sustainability Division, talks about the role Swiss polar research has to play and how Switzerland is stepping up its commitment to scientific diplomacy.

"The importance of scientific knowledge for diplomacy is increasing"

Mr Estermann, how does Switzerland benefit from diplomatic engagement in the scientific field?

In recent years, the link between science and diplomacy has been growing stronger. The importance of scientific knowledge for diplomacy is increasing – just look at climate diplomacy or international efforts to contain the current pandemic. At the same time, diplomacy can also support science by acting as a door-opener and helping to solve problems so that a particular project can move forward.

Switzerland is a small country – what can it do in the face of global challenges like climate change?

Switzerland was industrialised early on and is well integrated in the global value chain. This means that even a small country like ours can contribute to achieving the climate targets. It's not just in our interests to do so; I am sure that this is also an opportunity for our innovation-driven economy. Swiss universities are at the forefront of research into the causes and effects of climate change. The University of Bern, for example, has conducted groundbreaking research into the atmosphere's CO2 content over the last 800,000 years by analysing Antarctica's unique ice cores.

What has Switzerland's science diplomacy done concretely to advance polar research?

Switzerland was granted observer status in the Arctic Council in 2017. This was mainly due to our expertise in the field of snow, ice and high altitudes, which has direct relevance for polar research. Since then, the Arctic region has been attracting a lot more attention and we can follow these debates first hand. Researchers in Switzerland can also access the Council's scientific working groups. I see this as a great example of how science and diplomacy can benefit each other.